The history of the 87-year-old park

Gorge Metro Park is entering a new era in its vibrant and intriguing history. The Ohio Edison Dam is being studied for removal, and Summit Metro Parks supports the effort.

This is part one of two in a series on Gorge Metro Park. Let’s take a look at the park’s past.

Cuyahoga River formed by Glaciers

Gorge Metro Park is located in an improbable section of the Cuyahoga River. The river was formed about 12,000 years ago when the Wisconsin glaciers retreated to their northern origins. Only 100 miles long, the river is young, shallow and slow-moving — except in the gorge. The river falls a total of 700 feet in elevation from its headwaters in Geauga County to Lake Erie at its mouth. Over 200 feet of that elevation drop happens within a short two-mile section of the gorge.

About halfway along its current course, the young river encountered erosion-resistant sandstone at what is now Cuyahoga Falls. Here the south-flowing water was turned north by this mighty rock, giving the river its unique U-shape. The river was also forced to cut down through the pillars of the unrelenting bedrock, creating thundering cascades and exposing smooth rock ledges. The distinctive geology gave rise to a wealth of sturdy plants and animals that could survive in this cool, wet rock environment.

While the natural setting within the gorge has been seriously altered over the years by deforestation and human development, many of the original wildlife communities are returning. The park offers needed protection to some of the species that are endangered and rare.

Early Recreation in the Gorge

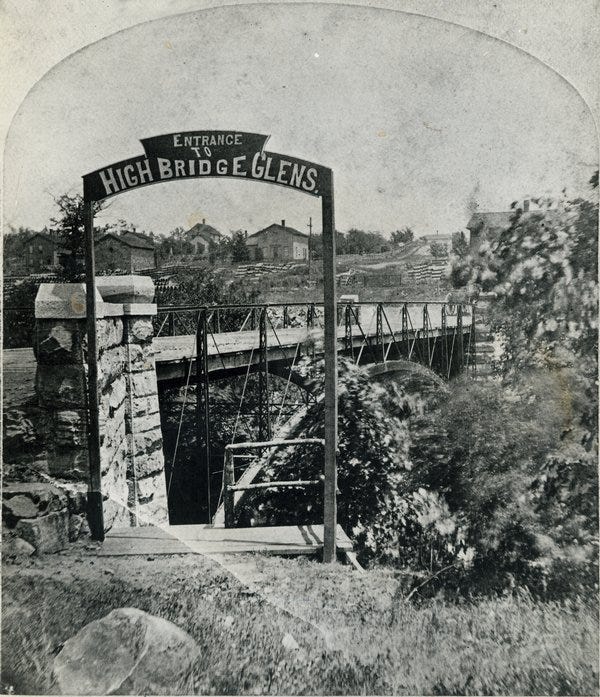

The dramatic topography dictated human use of the area. The region was used for recreation long before Gorge Metro Park. Its golden age came during the years of High Bridge Glens Park and Cave Park in the last quarter of the 1800s. The parks were a prominent destination for visitors, many who arrived on the lines of railroads and streetcars that interconnected Northeast Ohio. The main appeal of the parks was the setting. Visitors could dine or dance in the pavilions or ride on park amusements, including a very early roller coaster. While enjoying the attractions on the park’s high ground, tourists could marvel at the views of the Upper Gorge.

To access the Lower Gorge, visitors could descend the wooden steps with their picnics and parasols into the enchanted terrain. There, they would encounter trails, ferryboats and pedestrian bridges. Dressed in the formal attire of the day, suited men and bustled women could stroll through the towering ledges and follow the rushing water along the Grand Promenade to the Big Falls, a three-tiered 22-feet-high cascade. Their wonder and excitement was very much like Gorge Metro Park visitors today. However, today’s visitors encounter the Ohio Edison Dam, its pool and waterfall.

The River’s Power takes Center Stage

The importance of High Bridge Glens Park and Caves Park waned in the early twentieth century due to poor management and the decline of water quality. By that time, another aspect of the area’s topography had taken center stage: the river’s power.

Given the elevation drop of the river through Cuyahoga Falls, waterpower was always a fundamental factor in the city’s manufacturing sector. At one time, beginning upstream at Bailey Avenue, as many as seven dams captured the energy of the river for grist and saw mills, iron works and tanneries. By the late nineteenth century, the water’s role in electrical production had become as valuable as its mechanical advantage.

Like the rest of the nation, the region was captivated with the promise of electricity. By 1900, ribbons of streetcar lines crisscrossed Akron. Exterior street lamps lit up the downtowns, and many urban homes had electrical wiring. An insatiable appetite for electric power was in full swing during the Second Industrial Revolution. Production plants sprang up everywhere. With the success of electrical production at Niagara Falls in the 1880s, hydroelectric power became one of the great prospects for creating electricity. If there were a place for hydroelectric production in Northeast Ohio, it was certainly the gorge.

In the late nineteenth century, Northern Ohio Traction & Light Company (NT&LC) began purchasing land in the area of what would later become Gorge Metro Park. The company was looking to expand its production of electrical power and had an eye on harnessing the waterpower of the Cuyahoga River.

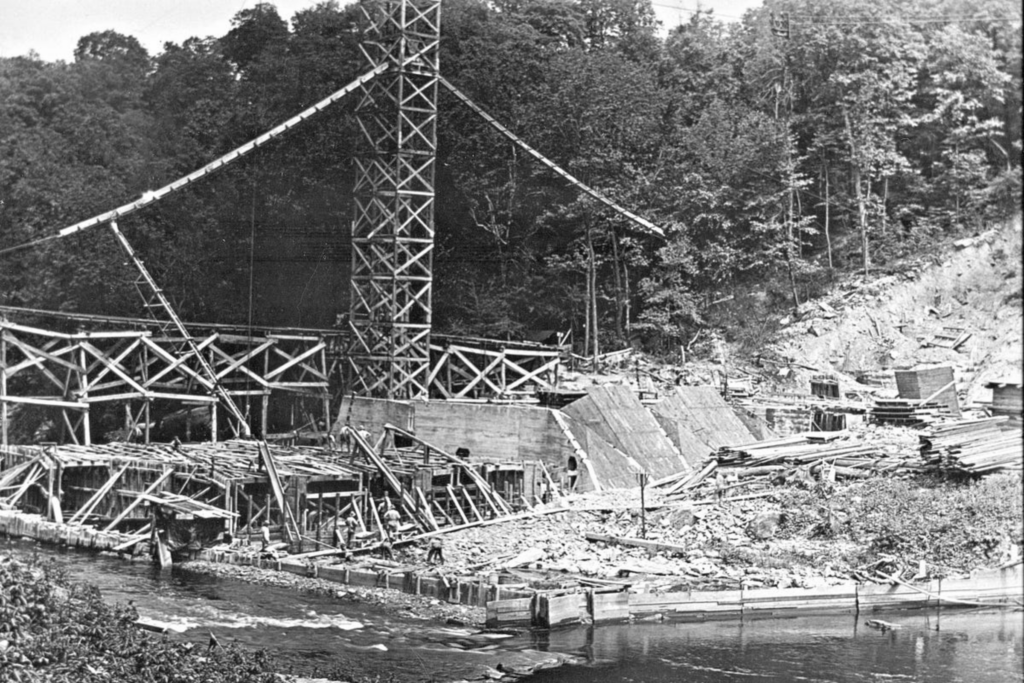

In 1911, NT&LC built a dam in the Lower Gorge of the Cuyahoga River. Like most dam builders, they took advantage of the natural fall of the river and built their dam on the Cuyahoga’s Big Falls. The power dam was 57 feet high and 420 feet wide. The dam pool extended over a mile upstream when flooded, provided cooling water for a coal-fired power plant built in 1912. Water pulled from the top of dam was sent a half-mile down stream to a hydroelectric generating plant. As water filled the reservoir behind the dam and the plants began to generate power, the lower portions of High Bridge Glens Park were drowned and the Big Falls disappeared.

The Glory of Gorge Metro Park

Even though Akron’s need for electrical power was clearly demonstrated, the effects of the dam construction distressed many residents. However, it was the dam itself that gave a major reprieve to recreation in the gorge. In 1929, the Northern Ohio Power Company, a descendant of Northern Ohio Power and Light, leased its land holdings to Summit Metro Parks. The utility retained rights to use and maintain the dam in its related power activities.

In its first century, Gorge Metro Park and the dam shared lives. The park is a popular place for visitors to picnic, exercise and enjoy the view. Located within both Akron and Cuyahoga Falls, the park draws hundreds of thousands of people annually. There is something for everyone throughout the year.

In spring, guests wonder at the coexistence of fragile wild flowers with unyielding and ancient rock. The coolness of the gorge offers relief from summer heat. In autumn, oak and maple trees fringe the gray ledges with a riot of color. And seeping water creates a “crystal palace” of icicles in winter. Glens Trail, Highbridge Trail and Gorge Trail provide nearly seven miles of easy to difficult hiking with stunning vistas of the gorge.

Hydroelectric production continued until 1958. The assembly had all of the right elements: 75 feet of hydraulic head, an 8 foot-diameter penstock pipe, upgraded turbines and a skilled engineering staff. Ultimately, the seasonal variations and unpredictable nature of the river’s flow worked against these advantages. The penstock and production plant were deconstructed in the 1970s.

Electrical production at the coal plant ended in 1991. In its early days, the plant had been state-of-the-art. But by the time of its closing, it was no longer cost effective. In 2009, the plant was razed. Between 1998 and 2009, various plans to use the Ohio Edison Dam for power generation were investigated. None proved viable. Since 1991, the dam that had once given rise to the park has lain idle with no future prospects.

Dams on the Cuyahoga River

Dams once dotted the Cuyahoga River and its tributaries. Early settlers built dams to grind grain and divert water for agriculture. In the 1820s, dams were installed to channel water from the river into the Ohio & Erie Canal. Until the advent of the railroads in the 1850s, the canal was the major route of transporting goods to Lake Erie and the Ohio River.

The industrial age brought new needs for dams and water. Dams popped up next to factories so they could use the Cuyahoga River’s water for processing, cooling and power. In addition to the Ohio Edison Dam, another hydroelectric dam was built in Cuyahoga Falls to capture the prospective power of the river’s flow.

By their nature, dams are temporary structures on rivers. They have a limited lifespan; time and the river will eventually lead to their end. While these barriers are intact, they have a significant, negative impact on water quality. They reduce dissolved oxygen, modify flow, trap toxins, prevent fish passage, interfere with sediment transport and alter the aquatic food web. They increase algal growth, reduce sediment-dwelling populations, vary water temperature, and obstruct many biological and chemical processes that are basic to the river ecology. In addition to their water quality impacts, the hydraulic waves created immediately downstream of dams are dangerous for paddlers and swimmers.

Prior to our understanding of the environmental impacts of dams and before our mid-twentieth century water quality crisis, society viewed dams as strictly beneficial. As cheaper, more dependable and less impactful methods were established to perform the purposes once served by dams, most of the dams on the Cuyahoga became obsolete.

Wondering what will happen to the Ohio Edison Dam in Gorge Metro Park? In Part II of this post, we discuss other dams on the Cuyahoga River that have been removed and possibilities for the future of the park.

Summit Metro Parks and a large coalition of community partners are working together to remove the dam on the Cuyahoga River in Gorge Metro Park. Learn about the efforts to Free the Falls.