Peg Bobel, Cultural Resource Specialist

One hundred years ago, Ohioans and the rest of the nation were still recovering from the 1918 influenza pandemic that took the lives of 675,000 Americans and upended the lives of many others. The “Great War” was also barely in the rear-view mirror.

But now things were looking up — in Akron, the growing rubber industries were hiring thousands of new factory workers and the city was growing by leaps and bounds. Much of the work, however, was dirty and backbreaking, with workers putting in long days. Nonetheless, progress was being made on shortening work hours and laborers found they had more leisure time. Popular nature writers such as John Burroughs were inspiring everyday folks to get outside and experience the physical and spiritual benefits of nature. With the crush of city life and the air turned sooty by coal smoke and factory fumes, urbanites sought out places to breathe fresh air, play in the open spaces and rejuvenate their spirits.

Out West, the young National Park Service was getting rooted, founded on a mission to both conserve natural and historic areas and “provide for the enjoyment of the same.” But Yellowstone and Yosemite were a long way away for most working-class Summit County citizens. Thanks to a few local visionaries, our Summit Metro Parks system was created in 1921 to meet that double need — to protect natural lands and provide access to safe places for families to gather, play and picnic.

Many good things come about when like-minded individuals come together with a dream. In 1921, renowned landscape architect Warren Manning was in the employ of F.A. Seiberling, having designed the gardens for Seiberling’s Stan Hywet estate. Manning in turn had brought young landscape architect Harold S. Wagner to town from Boston to help design another Seiberling project — Fairlawn Heights. Wagner had trained at Harvard’s Arnold Arboretum, and Manning had worked with renowned landscape architects Frederick Law Olmsted Sr. and his sons.

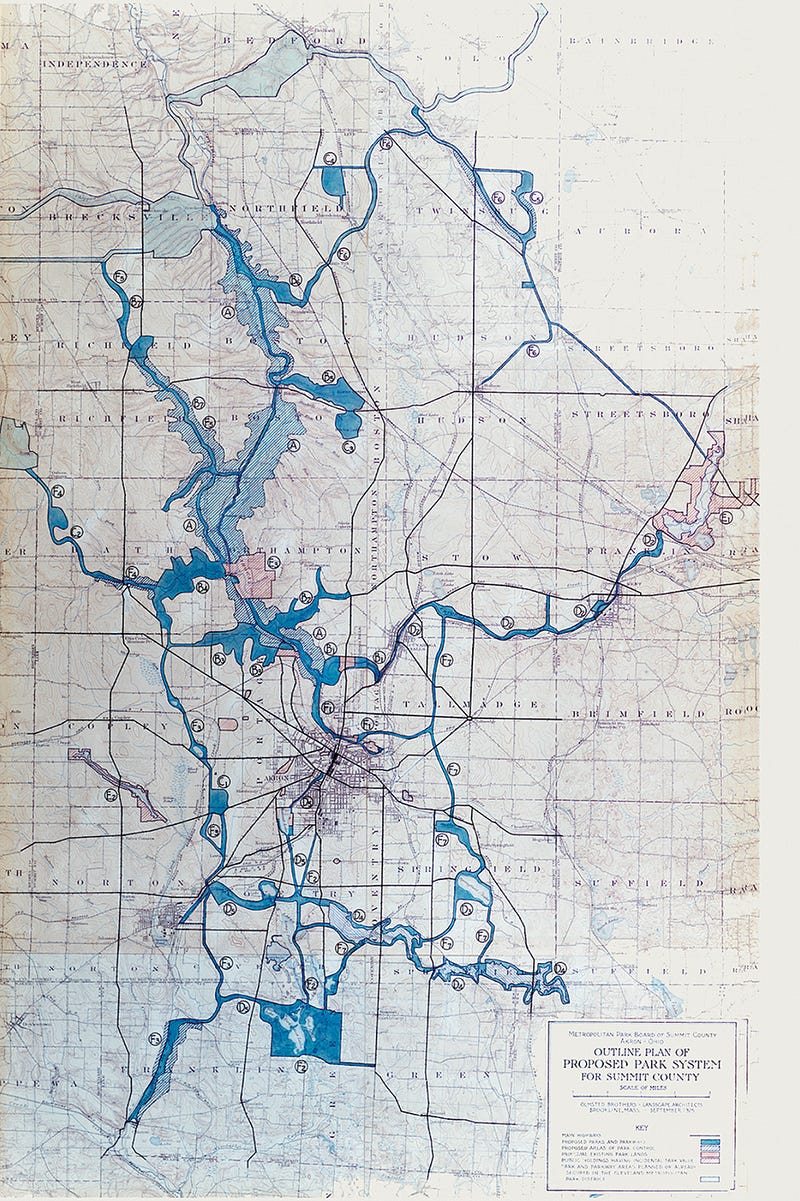

Meanwhile, up in Cuyahoga County, William A. Stinchcomb, the architect of the Ohio law giving counties the power to create metropolitan park districts, had hired the famed Olmsted Brothers firm to design Cleveland Metroparks’ “Emerald Necklace.” Stinchcomb recognized the importance of preserving natural areas around the city, referring to them as “a kind of ‘natural resource’ of ever-increasing value to the public” and urged the board of the newly formed Akron Metropolitan Park District to follow his lead. These personalities and their connections would all come together formally in 1925 — F.A. Seiberling being named a park commissioner, H.S. Wagner becoming the park district’s first director-secretary, and the Olmsted Brothers landscape architecture firm being hired to plan a park system for Summit County.

Seiberling wanted Frederick Law Olmsted Jr. himself to come to Akron, but that was not to be. Nonetheless, Olmsted assigned two of his finest landscape architects to the project — W.B. Marquis and E.C. Whiting. Both would stay with the Olmsted firm for years and are considered pioneers in landscape architecture. Their main challenge was choosing which places among the many beautiful areas they saw in Summit County to include in their recommendations for a park system. Some of their favorite parts of the county are now familiar to many park visitors as part of Summit Metro Parks: the valleys of Sand Run, Furnace Run and Yellow Creek, the Twinsburg Ledges, and of course the Gorge and Cuyahoga River valley.

Today, we celebrate these leaders who established our Metro Parks as we once again face a pandemic and experience renewed appreciation for green space. The story of Summit Metro Parks has evolved through one hundred years and continues to be written by the modern-day nature lovers of Summit County.

For more stories like this, check out Green Islands Magazine, a bi-monthly publication from Summit Metro Parks. Summit County residents can sign up to receive the publication at home free of charge. #SMP100